A Character Is As A Character Does.

“We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be” – Kurt Vonnegut.

Working on some crucial drafts of my own science fiction these past few months, pages of cool and witty dialogue came naturally to me, but certain character traits need to be developed further.

Revising various aspects of “Characterization” has unearthed some useful points which will be shared here. Besides, we have already complained about the lack of good character development in several recent movies during this past year, so it appears that some screenwriters would benefit from these tips too.

Before moving on, it would help if we had a working idea of how to define “character.” To be more than just a person in a movie or a book, a character must have “mental and moral qualities distinctive to an individual.” It signifies: “strength and originality in a person’s nature,” while to be “full of character” denotes the “quality of being individual in an interesting or unusual way.”

“Science fiction writers put characters into a world with arbitrary rules and work out what happens” – Rudy Rucker.

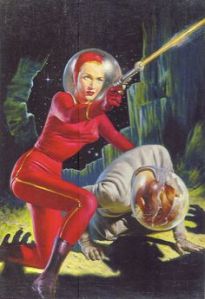

Take a look at the pic above. That’s fearless pilot: Ham Salad and his trusty sidekick: the Wookie Monster. The boys at the back look pretty familiar as well. Instantly, you recognised who they were parodies of. The characters of the galaxy’s greatest saga are so ingrained on popular culture because they were so well-defined.

Not only must you know where a character is going, it is imperative that we learn where they are coming from. A history or – if time and space is limited – a simple back-story becomes essential. It helps to flesh out what should become special characters.

Take a look, for instance, at Darth Maul: one of the factors that made Star Wars Episode I slightly less painful than Episode II. Groovy painted face and cool moves, sure, but sorely lacking any detectable character. How and why did he turn to the Dark Side? We are not given any knowledge, so – not surprisingly – when he is sabred in half, we just don’t care.

Incidentally, his opponent in the lightsabre duel midway through this flashy yet flat misfire was a Jedi played by Liam Neeson named… umm… (Can’t be bothered to Google it – that’s how useless Neeson’s “contribution” was). Here was somebody with even less “character” than Darth Maul, and he had much more onscreen time! Unbelievable!

At least Groovy-Painted-Face was a figure of action. This is a useful reminder that characters have a better – more immediate – chance of fascinating us by what they do. And not just the process of the action itself, but the anticipation of how a certain character will act, or – more crucially – react.

“What is character but the determination of incident? What is incident but the illustration of character?” – Henry James.

In other words, plot and character are one and the same, but don’t value plot over character. It is said that a good science fiction story centres on a single idea, yet that idea cannot drive the plot alone. Characters are required to deal with that idea – they make it relevant; they make the material matter.

A physical description of a character is NOT characterization.

Plenty of writers list physical attributes as if it is imperative that the reader should have an accurate image of them in their mind’s eye. Rather than simply apply labels, provide more details. In science fiction, is it relevant that she has green skin and he’s got tentacles? Probably not, unless it drives the plot somehow.

Apart from the fact that Gamora (from last year’s smash hit: Guardians of The Galaxy) has green skin, how can you describe her? She is a nimble fighter in the movie – yes, but that makes her merely an action figure, not a character. To compound the problem, she has to confront her half-sister: Nebula who is… well, someone who shouts and struts around a lot. Their fight turns out to be just as bland and superficial as they are. We are too easily reminded of the two nonentities we had trouble describing in the previous paragraph.

Let’s end this paragraph on a more positive note: one particular trait of characterization exclusive to the science fiction genre concentrates on the responses of specific characters to a change in environment, caused by nature or the universe, or technology. What will draw readers to these characters is how they cope with that change.

“Characters, if they are strong enough, can evolve into pseudo-autonomous beings who are resilient enough to lead the author through the twists and turns of plot. It can be fun to travel this way, because we never know what’s around the next turning” – Teach Yourself: Write A Novel.

Characters – especially in this genre – need to be aspirational – the kinds of heroes readers/viewers would want to be themselves. Even anti-heroes should have redeeming features. Whether it be charisma, wit, style and/or intelligence. Ideally, they have to be the character you love to hate.

“Character” is internal and shows up in the good – and bad! – choices made under pressure. Before making your characters leap from the page, they have to affect you first. If you care about how they develop, the reader will care about them too. By all means necessary, they must engage with readers on an emotional level.

You should sympathise with them as well as empathize. Who has not shed a tear for the homesickness of ET or the last desperate hour in the short but very bright life of Roy Batty?

In this case, it is amusing to add one of the most important tips for creating any kind of fiction: characters need authentic underlying humanity. It’ll be a really nifty trick if you can apply that to any of your alien characters!